- Home

- Jane Lotter

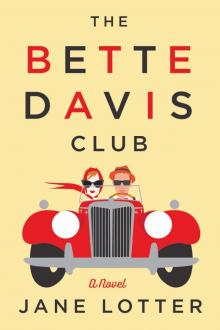

The Bette Davis Club Page 6

The Bette Davis Club Read online

Page 6

“I know something about architecture,” Tully says. “And I have to tell you, I don’t care for your line of work.”

A chill shoots through my body, but it isn’t from eating ice-cream.

“‘Architectural salvage’ is an oxymoron, okay?” Tully says. “It’s ghoulish, gives me the creeps. You salvage people don’t do anything at all to preserve history. You stand around, hands in your pockets, while they knock down some great old landmark. Then you rush in with price tags and a wheelbarrow.”

My ice-cream is nearly gone. I crunch down hard on the cone.

“You carve up these incredible old places and sell the body parts to whoever has the dough,” Tully says. “And they always end up in somebody’s stupid McMansion or in the boardroom of some big law firm. That’s not salvage. It’s sacrilege.” He glances at me as though I’ve just been revealed as a torturer of small furry animals.

“It’s slightly more complicated than that,” I say.

“Yeah?” Tully says. The car picks up speed. “How’d you get into that business?”

“Long story,” I say, determined not to tell it. Who is this person with the five o’clock shadow, plonked down in my father’s car? Why should I explain my life to him?

“So tell me,” I say, “while I’m looting America’s treasures, how do you occupy your time?”

“I’m a writer.”

A light goes on, and I picture both Malcolm Belvedere and Charlotte’s husband, Donald, who works with scriptwriters. “Screenplays?” I say. “You write for the movies?”

“I’m writing a book,” Tully says. “That’s how I met Georgia. I came out here to do research, and we met at a party.”

“What’s your book about?”

“Miniatures. Dollhouses and things.”

I laugh. “Dollhouses?”

“Yeah,” Tully says defensively. “Something wrong with that?”

“You have to admit,” I say, “it’s an unlikely subject for a grown man to take an interest in.”

“Not for me it isn’t,” Tully says. “It’s a collection of interviews and essays, with some history thrown in.”

The topic seems silly to me. I can’t keep amusement out of my voice. “I didn’t realize there was any history to dollhouses,” I say.

“No?” Tully says. “Then read my book when it comes out. That is, if you can read.”

Is Tully taking his anger at Georgia out on me? Well, look out—because I have anger of my own.

“Oh, I can read,” I say slowly. “The question is, can you write?”

“Forget it,” Tully says. We bounce over a pothole. “It’s obvious you’re clueless about dollhouses—just like you’re clueless about architectural salvage and clueless about Cary Grant.”

I no longer care if Tully’s having a rough day.

“And you,” I say, “know nothing about architectural salvage, nothing about Cary Grant, and fuck-all about me.”

He glances over at me. His eyes are blazing. “Your name’s Margo, right?”

“Correct.”

“Well, maybe you don’t live in England anymore, Margo, but you’re sure an uptight Brit.”

I toss what’s left of my ice-cream cone out into the desert. “Stop the car,” I say.

“What?” Tully says.

“Stop the car.” I claw at my scarf, ripping it from my head. “I need air.”

“We’re in a convertible,” Tully says.

“I’m suffocating,” I say. “I can’t breathe. I need a cigarette.”

Tully swings us to the side of the road and brings the car to a sudden, squealing stop. Our bodies rock backward, then forward. We sit there, in the middle of nowhere, engine idling.

I fumble for the handle and push the door open. I swing my legs out onto the ground and stand up.

“Aw, come on,” Tully says. He pushes his glasses back up on his nose. “We’ve got to keep going. I didn’t mean—”

I hold up my hand. “I know we need to keep going,” I say. “But right now I need air, I need a smoke, and I need a few minutes alone.” I’d also like a drink, but forget that. I reach back into the car for my tote bag, which contains my cigarettes.

Tully switches off the engine. When I grab for my bag, he puts his hand on my arm. “Margo, don’t go. Stay here and I’ll . . . open a window.”

“Ha-ha,” I say, pulling away from him. I turn and walk away.

“Why do women run from me?” he calls. He gives a bitter laugh. He’s laughing at himself, I know, not at me. Laughing even though there’s nothing funny about being dumped on your wedding day, nothing funny about sitting alone in a bright-red Love Machine on a deserted highway in the California desert.

I walk off toward a cluster of rocks. One large rock, bigger than the rest, has a scooped-out area, almost like a seat, and I rest against it. The stone is gritty and warm from the sun. I reach into my bag for my cigarettes and lighter, but my fingers brush Charlotte’s cell phone. I stop. I forego the tobacco. I pull out the cell phone instead.

I punch in the number of Dottie’s shop in New York. The phone rings twice, then Dottie answers. “Older Than Sin, French Art Deco and Collectibles.”

“It’s me. I’ve been kidnapped.”

“Margo! I’ve been thinking about you. How was the wedding?”

“There wasn’t one. I’ve ended up honeymooning with the groom.”

She laughs. “Right. Really, how are things?”

“I will tell you. Georgia jilted her fiancé and fled to Palm Springs. Charlotte hired me to go after her. So now I’m riding around in my father’s 1955 MG. Actually, the car part is nice. Oh, and the bridegroom is my chauffeur.”

There’s a moment’s silence. “Chérie,” Dottie says at last, “you aren’t by any chance on a bender?”

“I wish. More like I’m being held sober against my will.”

“Merde.”

“Exactly,” I say.

“Merde,” she repeats. “Darling, I’m sorry, but we’re about to be interrupted. There’s a young couple looking in the window. Bags of money, if I’m not mistaken.”

“Why bother?” I say. “Young people are all broke now.”

“Not the ones who own start-ups,” Dottie says.

Dottie is a wizard at discerning disposable income. I imagine her straining to look out the window, giving the young couple the once-over. “Yes,” she says, “these two are cash cows, coming into my barn. Can you hold?”

I hold. Dottie puts the handset on the counter, and I hear her talking with the customers. From the sound of their voices, I don’t need to see them to know what they look like or where they’re from. Seattle, probably. I picture the corduroy pants, the cotton turtlenecks.

“Well,” the man says, “our accountants say we better start a collection.”

“Something world-class,” the woman says. “Paul Allen already did rock and roll. That’s antique and all, but we want to do something really, really old.”

“I see,” Dottie says. “Of course, this establishment specializes in French Art Deco of the early twentieth century. Did you have a specific period in mind?”

“We like the chocolate period.”

“The . . . chocolate period?”

“Fancy stuff. Princes and princesses.”

“The fancy chocolate period. No plain vanilla for you.” By the strain in Dottie’s voice, I imagine the wheels turning in her head. “You don’t by any chance mean . . . no, you couldn’t. You don’t mean, rococo?”

“That’s it, row cocoa.”

I can almost feel the air rushing out of the room. Then I hear Dottie’s voice again, deflated: “Other side of the street, half a block down. Good day.”

There’s the sound of the shop door opening and closing, then Dottie is back on the line. “Did you hear that, darling?”

“I did,” I say. “I’ve told you before. The television screens are getting larger, but the heads are getting smaller.”

“Yes, bu

t I’ll have my revenge. I sent them to Starbucks. Anyway, we’re alone now. Tell me about your niece’s fiancé. Do you like him?”

“Not particularly.” I slump against my boulder. “His name is Tully, and I wish he’d fall out of the car.”

“And why is that?”

“He has a chip on his shoulder.”

“That’s understandable, isn’t it? You say he was left at the altar—”

“He’s a know-it-all. He said Cary Grant was gay.”

Dottie laughs.

“It’s not funny.”

“It is a little. But I can see that it’s not the best topic for the two of you to start off on.” Dottie sighs. “Still, he must have some charms, or your niece wouldn’t have agreed to marry him.”

“He probably held a gun to her head. The minute Georgia went to change into her wedding dress, she saw her chance for escape.”

“Does the man have any interests? Besides getting married.”

“Miniatures or something. Dollhouses. He’s writing a book about them.”

“I see. Well, it’s not that far from Los Angeles to Palm Springs. How long have you been in the car?”

“Days. We’re turning into the Donner Party. I’ll have to toss out my luggage as we cross the desert. We’ll end up drinking water out of the radiator or eating each other for lunch. And he’s so small, it’d be more like brunch.”

“Margo—”

“About two hours.”

“Then you’re nearly there. It’s a lovely town, have you ever been?”

“No, it’s terra incognita. I’m hoping a miracle happens and I don’t have to go.”

“It’s the epicenter of mid-century modern,” Dottie says. “All that 1950s and ’60s glamour and Rat Pack retro. It’s also the playground of movie stars: Dietrich, Gable, Harlow. Of course, those people are all dead. And some things have changed.”

“Such as?”

“I don’t want to harp on this topic. But it’s no secret that Palm Springs has one of the larger homosexual populations in the country.”

“Goodie,” I say. “I’ll drop Tully at the first leather bar we come to. They can stretch him on one of those racks.”

“Margo, be serious. Is he really that small?”

“No.” I poke a Ferragamo-clad toe in the sand and make circles with my foot. “He’s medium height, nice hair. He’s good-looking, actually. If you ignore the rest of him.”

“Uh-huh. Be careful.”

“About what?”

“Je ne sais pas. It’s an all-purpose alert.”

A short time later, Tully and I are back on the road. There’s an uneasy, unspoken truce between us as we head east on Highway 111.

The San Jacinto Mountains are not high, and the MG crosses them easily. On the other side of the mountains, the Coachella Valley opens up before us. The landscape once again becomes the scrubby flatland of the desert, dotted with cactuses, sagebrush, and yucca plants.

We soon reach the outskirts of Palm Springs. The first real building we pass is the city’s official tourist center, a 1960s space-age structure with a soaring triangular roof.

“I suppose we should find a hotel,” I say. These are the first words I’ve spoken to Tully since we had our spat at the side of the road.

Tully shakes his head. “Charlotte booked us into a place downtown. La Vida Loca.”

We cruise farther on, and then we see it: La Vida Loca Resort and Spa. It’s a large mid-century modern building, two stories tall, with a flat roof. Sunlight bounces off its white angular walls and striped awnings. Tully turns us onto a circular drive lined with palm trees. We pull up to the valet parking.

A young woman in a polo shirt and neatly pressed slacks rushes to open the car door for me. Another woman attends to our luggage. I thank them both. I step onto the carpet that leads into the resort. Tully comes round to my side and together we walk, rather like the honeymoon couple, into the main building.

The lobby glitters with starburst chandeliers, terrazzo floors, and candy-colored 1950s-style furniture. Off the lobby, through a wall of glass, there are well-tended grounds, tennis courts, a swimming pool.

It’s been three hours since we left Los Angeles. Now we’re in one of America’s most popular vacation spots, bathed by sun and luxury. But none of it has the slightest appeal to me.

I want only one thing: to find Georgia and get this business over with. After I do that, I will walk away with a large sum of money, walk away from Southern California, and walk away from Tully Benedict. That’s all the incentive I need.

CHAPTER FIVE

DREAMY MONKEYS

It is not true that misery loves company. What misery loves is a double martini. When Tully goes to the front desk to register, I straighten my clothes and smooth my hair. Then I walk across the lobby, headed for the hotel bar. My top priority—my number one goal—is to track down Georgia. But first I need a pick-me-up.

Like the rest of the hotel, the lounge dates from the 1950s, but it has an added dude ranch twist. Spurs and lucky horseshoes hang from the walls. A bowlegged cowboy in a large framed cartoon drawing waves out at the world saying, “Howdy, Pardner!”

The room is small and crowded. And when I say crowded, I mean it’s jam-packed with women, nothing but women. The air hums with the high-pitched buzzing of dozens of females all talking at once. It’s a sound that reminds me of meals in the dining hall at St. Verbian’s.

The only vacant seats are at the bar itself. That would be all right except the bar stools aren’t stools at all. They’re saddles. Western-style saddles, made of highly polished tooled leather. To get served, you have to swing one leg over and mount up. And now, because I very much want a drink, I do just that.

The bartender, a young man in jeans and a cowboy shirt, is down at the end of the bar, taking glasses out of the dishwasher. He turns and sees me and gives a little hi-howdy wave. But when he comes over to take my order, I realize he’s not a man at all. He—she—is a woman. A flat-chested, twentysomething woman with short hair.

“What can I get you for?” she says in a friendly drawl.

“An English saddle,” I say.

The bartender hesitates, as though considering whether I’ve requested some sort of cocktail. Then she takes my meaning. “Right,” she says. She grins. “Had a gal in here today who claimed she only rode bareback. Course, she drank so many dreamy monkeys, in the end she fell off her mount. Her compadres had to carry her to her room.”

I smile. “And what, may I ask, is a dreamy monkey?”

The bartender leans in, as though sharing a confidence. “It’s a dog’s breakfast,” she says thoughtfully. “You throw everything in the blender—vodka, crème de cacao, ice-cream, bananas, the whole taquito. A dreamy monkey is like a boozy milkshake for kids, for young folks who ain’t got the hang of liquor.”

Myself, I long ago got the hang of liquor.

“Pass on the milkshake,” I say. “But I have just crossed the desert, and I’d like a large martini.”

“You bet. Gin or vodka?”

I rather like this flat-chested bartender and her cowgirl ways. My leather saddle creaks underneath me as I settle in. “Gin,” I say. “Gordon’s, if you have it.”

Half an hour later, the bartender and I are pals. Her name is Ruby. She lives in a house out in the desert with her partner, Vera. Together, Ruby and Vera own a horse, a dog, and several cats.

Ruby is friendly and easy to talk to and (I’m beginning to realize) possibly thinks I’m gay. Well, why not? After all, I’m convinced she is. Not to mention I’m sitting in a bar that for some reason is chockablock with talkative females, every one of whom appears to be homosexual.

In less than a day, I’ve been mistaken first for a newlywed and now a lesbian. What other surprises await me, I can’t imagine.

“Is it always this busy?” I ask Ruby over the noise.

“Nope. We do a good business, but this”—with a sweep of her hand she indicates the packed

room—“is because of the Dinah. That and, you know, the tournament.”

I don’t know. What Dinah? What tournament?

“Course, they changed the name a while back,” Ruby says. She mixes a pitcher of margaritas, draws several beers, and continues conversing with me, all without breaking her stride. “It used to be named for Dinah Shore. But anymore they call it the Kraft Nabisco Championship, or some such thing. You know about it, right?”

“Afraid not,” I say.

She looks at me like she’s trying to figure out if I’m kidding. “It’s world famous,” she says. “It’s the Masters of women’s golf. You honestly never heard of it?”

“Sorry,” I say.

She narrows her eyebrows, like she still doesn’t believe me. “They hold it a few minutes from here, in Rancho Mirage. And every year, same time as the tournament, there’s Dinah Shore Weekend here in Palm Springs, and I know you’ve heard of that. The Dinah is the biggest get-together of dykes you ever saw, the biggest lesbian party in the world. Last year, fifteen thousand gals showed up.”

While I’m digesting this piece of news, Ruby leans toward me and says in a low voice, “Don’t tell nobody, but I’d work the Dinah for nothing.”

I laugh. Ruby continues filling me in. “Every gal who comes to Palm Springs during Dinah Shore Weekend loves golf or women. Or both.” She looks me up and down. “You golf?”

“Sorry, no.”

She gives a sly smile, and I realize I’ve just confirmed for her that I’m gay.

I decide to change the subject. I compliment Ruby on her cowboy shirt with the smile pockets. (You don’t often see those in New York, unless you’re watching the DVD of Midnight Cowboy.)

“Thanks,” she says. “Vera bought it for my birthday. It’s from one of the used clothing stores, quite a few of them in town.”

Ruby eyes my own outfit. “If you like clothes,” she says, “you might want to visit the shops. There’s one place, near here—Mommie Dearest. It’s the best of the bunch. They got gowns and dresses that belonged to movie stars, millionaires, celebrities. Everything in there is secondhand, but people spend thousands on it anyways. Not me and Vera so much, but you know—”

The Bette Davis Club

The Bette Davis Club